Fishing

Out Of Newlyn

By J. Kelynack

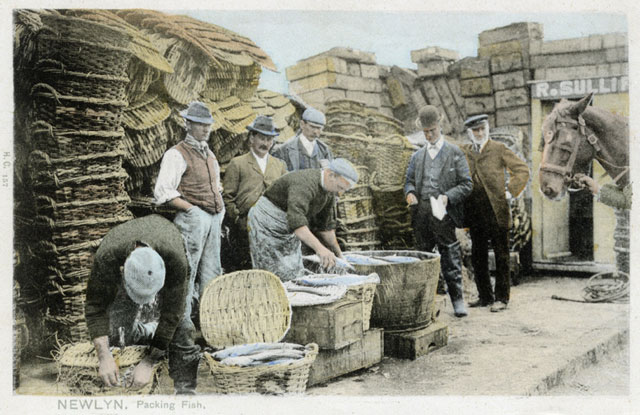

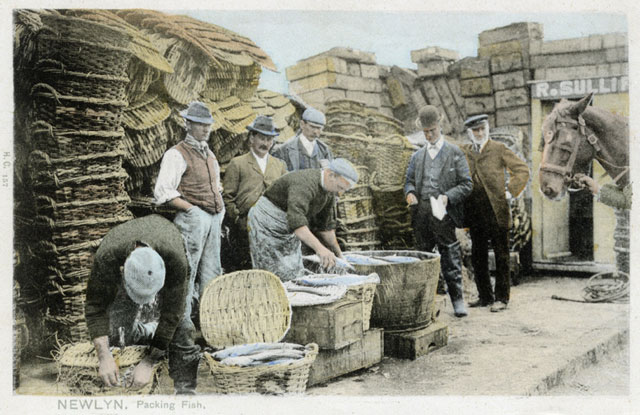

NEWLYN

West nestles at the foot of a hill on the N.W. shore of Mount’s Bay. It was

once a fishing village, but since the formation of the new harbour it has become

popular and important as a port, and is now linked up with Penzance.

Street-an-Nowan

and Newlyn Town are now connected by a good broad road. At one end stands a big

Fish Market.

From

the river to almost the southern extremity of Newlyn there is a commodious and

safe harbour formed by two piers, North and South, built about fifty years ago.

The need for a harbour at Newlyn was felt because Penzance Harbour was so

dangerous to enter in southerly gales, and there was not always sufficient water

to take boats in, while Newlyn could be reached in all weathers and at all

states of the tide. To-day the harbour affords shelter to fishing and trading

craft from various parts. Steam mackerel-drifters from the East Coast lie side

by side with Belgian boats, crabbers from Brittany and Brixham trawlers.

Steam-ships discharge cargoes of coal, and alongside the South Pier are others

being laden with stone (blue elvan) for road-making.

Comparatively

few local fishing-boats are observed. They have been ousted by bigger and more

up-to-date vessels, which can go faster and farther to fishing grounds and also

stay longer before bringing their catches to market for sale. From 45 to 50

years ago a fleet of about 200 mackerel.drifters sailed from Newlyn to the

fishing grounds, but these boats have gradually dwindled down to about 20.

Mackerel

fishing was carried on from March to June, off the Scillies, Ireland and France.

Each lugger was manned by seven men and carried a train of 50 nets, each 5o

fathoms long—12,500 ft., about 2 miles.

In

the early parts of the season, mackerel were caught near enough for landings to

be made every day or two; but later, when the fish were farther off, nearer the

Irish and French coasts, the takings were borne to St. Mary’s, Isles of

Scilly, there sold by salesmen from Newlyn, and purchased by buyers also from

the home port, the salesmen and buyers spending the week from Monday to Friday

at St. Mary’s. In succession three ships, the Queen of the Bay, the Lady of

the Isles, and Lyonesse conveyed all the fish to Penzance for despatch to the

Metropolis by rail.

Lists

of the various luggers and their respective catches were sent by the salesmen

from Scilly and taken by the waiting messenger with all haste “home” to the

officer of the firm for which he worked. Here an eager crowd of children, and

often women, waited to know whether the boat concerned was “listed,” some

going away lightheartedly, others despondently, at the result. On Saturdays

the money realised from the week’s toil was shared by the captain at his home,

the members of the crew being present.

All

seasons, even in those days, were not prosperous. Some dragged on and on with

very poor catches. When the lesson was read from Numbers XXII. in Church, one

would hear the remark, “Baalam and Balak was read in the lesson to-day: no

more fish now, the season is over This would just mark the time when big catches

of fish could no longer be expected.

As

soon as the season ended the boats were “belayed,” and all nets were washed,

dried, repaired, and stowed away in the loft until required.

Nets

were preserved by “barking” or tanning with catechu in huge vats, then they

were spread in the fields, on the beaches, or on the grass at the foot of St.

Michael’s Mount to dry: children delighted in sailing to the Mount or to the

beach under the Promenade, Penzance, with the nets. That is past history. Few in

Newlyn to-day would have participated in that pleasure.

Next,

all the big boats were fitted out for the Irish herring-season. Every boat was

scraped, caulked,- tarred and painted, nets were placed in the “net room,”

and provisions to last a few days taken on board. Bags of hard ship’s-biscuit

and fresh beef from Penzance formed the bulk of the food store.

The

boats, now arrived off the Irish coast, fished out of Howth. The men had their

favourite resorts. Newlyn men visited Kingstown, and Mousehole men Ardglass, on Sundays.

(see editors note).

As

the fish travelled North, the boats followed them and fished from the Manx

ports. Peel, Douglas, Derby-haven and Castletown were favourite resorts.

Still

the herring travelled farther North, and the luggers, arriving in the Clyde,

entered the locks through which they were towed to the East coast. Eyemouth and

Berwick were the first ports of call.

Southward

they came down to Hartlepool, Whitby and Scarboro’, the North Sea herring

ports. On making the homeward voyage, which took about one week with fair wind,

a few boats fished out of Lowestoft, also. More recently Mount’s Bay boats

have gone as far as Aberdeen for the herring-season.

The

fleet generally arrived home for Paul Feast, in October. What treasures were in

the boat’s lockers and sea-chests for those at home! They were gradually

collected: liquorice and broad-figs from the Isle of Man, glass and china, dolls

for the girls, and toys—such novelties and strange sweetmeats!

During

the summer, seining was carried on in Mount’s Bay in large rowing-boats built

for the purpose. Mackerel-seining was pursued in June. A “school” of

mackerel was a fine sight. On a smooth sea there first appeared what one might

take for a gentle breeze ruffling the surface. This spread and deepened until

the whole became a splashing, tumbling mass.

Smaller

luggers, “pilchard.drifters,” were prepared for catching this specially

Cornish fish, the pilchard season lasting from June to September.

Pilchards

were caught in Mount’s Bay, the pilchard drifters leaving the harbour at 4

p.m. to arrive on the “ground” and “shoot” nets at sunset.

Each

boat had a crew of three men and carried 12 nets, each “250” long (25

fathoms). When the nets were shot they extended for more than half-a-mile, and

to these the boats “rode” and drifted with the current. No prettier picture

was ever witnessed than that from Gwavas Hill, on a summer night about 9-30 or

io o’clock, when all the lights of the little pilchard-drifters, dotted about

under a

At

10.30 or 11 p.m., the nets were hauled in, and the boat made for port. One often

heard a quiet call from a watcher on the cliff, “What fish have ‘ee got ?“

and the equally subdued reply in a deep voice, so many “hogsheads,”

“thousands,” or “hundreds,” and occasionally “Not a life !“

At

times a boy or girl, or two, or a visitor, would be taken out

“pilchard-driving.” What an experience was theirs when a good catch rewarded

the fishermen’s efforts, to see the glistening fish being drawn into the boat

out of the deep, dark water! These pilchards were all disposed of in the early

mornings to jousters, or to local fish-curers.

During

September and October pilchard-seining took place. This was one of the most

exciting and interesting of all the seasons. The pilchards first made their

appearance off Newquay, then gradually travelled down all round the coast to

Mount’s Bay and on to Mevagissey. The seine-boats for Mount’s Bay were kept

at Gunwalloe, Mullion and Cadgwith, the fishery having died out at Newlyn,

Mousehole and the Mount, formerly all dependent on it. When news came that the

pilchards had passed Newquay, the “huers” at Mullion were ever on the watch

on the cliffs.

As

soon as a school was sighted, the signal was given to the crew of the

“seine-boat,” a long open rowing-boat with a great hump of net in the

centre. Beside her were the “tuck-boat” and “cock-boat.”

All

hands were in readiness, and at the sign speedily pulled out from the shelter of

some rocky headland to the spot indicated. Bonfires were lighted to signal to

the Western Shore for boats to come for fish, and as soon as the blaze was seen

the cry went up, “Hevva! Fire in Mullion!”

Such

a commotion in the sea met the eyes of the delighted seiners !—Here were

millions of pilchards dancing and leaping out of the blue water and lashing it

to fury. What a prize if the men are quick enough! They encircle the

“school” with the heavy seine and draw the ends securely together; to keep

the fish in the enclosure the boys in the “cock-boats” frantically splash

with their oars, and plunge big round stones slung on ropes up and down in the

water to the cry of “Plouncy, boys! Plouncy !“

Meanwhile

the encircling net is drawn closer and closer, and those in the “tuck-boat”

dip up basketful after basketful of silvery fish into the waiting huggers, whose

crews, on hearing the familiar cry of “Hevva !“ carried from street to

street, emptied their boats of nets to fetch a load. They fill up till they are

deep down to the gunwale in the water, and so return home across the bay.

Eager

hands await the harvest of the sea, and the precious burden is carried, by men,

women and children up the slip-ways and stiff streets, to the cellars in

readiness to receive them. Horses and carts toil up the inclines by the aid of

torches as the night advances. Women bend under the weight in their cowals. One

might see three persons carrying two baskets of fish between them, and children

following, picking up what fell out of the baskets.

Now

let us look at the cellar, It is a big stone-paved court with lofts, or the

dwelling-house, over part; these being supported by tall granite pillars. The

covered portion is paved closely with very small oval stones in cambered strips,

divisions being made for drainage with long narrow pieces of wood. The rest is

open to the sky. About four or five feet above the pavement, and at intervals

along the walls, are square apertures to accommodate the ends of long beams, or

“pressing-poles.”

When

the pilchards reached their destination the whole cellar was illuminated by

candles, and everyone was busy till far into the night. As soon as day-light

appeared, men and women were again in the cellars to start the curing of the

fish. “Bulking” was the first process. This meant the forming of huge piles

of pilchards on the small paving stones, in alternate layers of fish and salt,

the outer row showing all the fishes’ heads. These “bulks” were allowed to

remain 3 weeks before the fish were considered cured and fit to “break out.”

Now the salted pilchards, known as “fairmaids,” were washed in a kieve, or

huge wooden tray having a grating in the bottom through which the fish scales

could drop. From this the pilchards were lifted on a big griddle into a wooden

stand, having a barred bottom, on high legs. This stand containing the fish was

carried by two men to the women already waiting to pack the “fairmaids,”

into hogsheads, numbers of which were standing in readiness against the walls,

under the apertures.

Each

woman placed as many fish as she could on her open palm in the shape of a fan

and placed them in the hogshead, head to cask, until the circle was complete.

The centre. called the “rose,” was filled in alternately head and tail, this

being repeated until the cask was full. A heavy wooden cover called a

“buckler,” was next placed on top, with blocks on its inner side for

leverage. A long “pressingpole,” inserted in the aperture above and

projecting some distance beyond the cask, was weighted at the end by means of a

big, rounded “pressing-stone” hung by its hook on a rope sling, and so the

fish were pressed for 2 or 3 hours. At the end of this time the cask needed a

refill. 24 hours later a further repacking was necessary, and at the end of two

days the final “back-laying” was done. - This time all the backs of the fish

were uppermost. Two thousand “fairmaids” were now in each hogshead, and the

whole had a last pressing before the cooper came to “head in” the cask.

Buyers’ agents next came to examine the fish, which were weighed, and, if

approved, passed and stamped with the purchaser’s name, usually “Bolitho

& Co.” They were then despatched to their destination, Italy, in

schooners, and later, steamships.

Each

hogshead of fairmaids fetched about £3. Everything from the pilchard was

valuable. Nothing was lost. The oil obtained through pressing, was sold for

refining and came back as—who knows? Drugs, the scum, were sold for

lubricating engine-wheels. The salt, used in preserving the fish, was sought

after by the farmers for manuring their land.

At

the settling up of the season’s accounts, the “seines’ account” took the

form of a feast at one of the inns. Punch was the drink, and the toast was,

“Long life to the Pope, death to our best friends, and may our streets run in

blood !“ No wonder such a toast was pledged when the pilchard industry was so

remunerative.

Editors note:- J Kelynacks grandfather was a partner in a fishing boat with my great uncle Henry Vingoe. In 1840 they were fishing the Irish sea and this report appears in the Collectanea Cornubiensia by George Clement Boase.

Pg. 1452: under "Recollections of the Irish Church". written by Richard Sinclair Brooks M.D., Pubpilshed by Macmillian & Co. 1877.

"Contains under date of 1840 Notices of John Kelynack, Henry Vingoe, Thomas James (who was afterwards drowned) Nicholas Wright, Hitchens, Boyns and of Simmons (who died of consumption). These men were in Ireland fishing and Brooke held a service on board their boat at Kingston Harbour."

Sandra Pritchard nee Vingoe. Return to Text

![]()